Hello everyone. My newsletter this week is focused on writing. I hope those of my readers who are not writers themselves will enjoy a peek behind the scenes of the writing life. And, for the writers among you, I hope you find something new to think about.

(As a quick aside, I am aware that reading aloud isn’t possible or pleasurable for some people. Please leave aside any advice that isn’t suitable for you or your needs.)

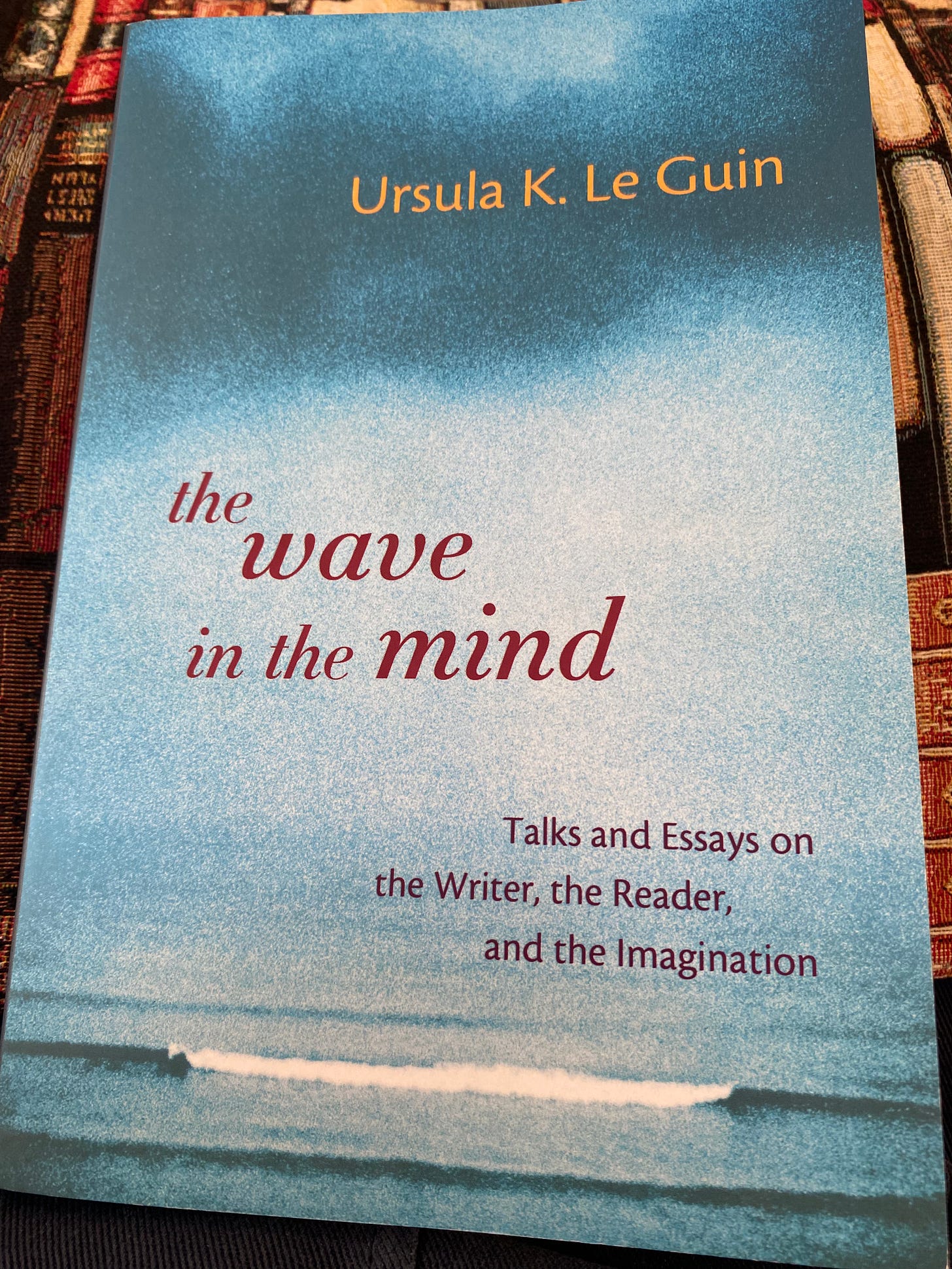

Reading Ursula K Le Guin’s The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination

Last month I was lucky enough to attend a reading group session run by Art in the Nuclear Age. Thank you to Vicki Lesley for letting me know about it. Do check out Vicki’s wonderful documentary film The Atom: A Love Affair (currently available on Netflix) and her Substack (Meandering over the pebbles) where she is currently posting a series called The Atom & Us in which she interviews artists, campaigners and industry experts who she got to know during the making of her film. You can find the first interview here.

The reading group was discussing the work of Ursula K Le Guin, particularly her essay collection The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination. As usual, I hadn’t finished the book when I joined the session, but, as I was mostly listening to the fascinating conversation while driving home from my writing group at the library across the city and therefore couldn’t join in much, my inability to contribute didn’t matter.

Book groups and childhood favourites

Another book club I attended in November was for my Discord server where I met

my partner. I did manage to finish (re)reading this book (by the skin of my teeth), mainly because The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry is only 109 pages long. After a thought-provoking discussion of Le Petit Prince we talked about books that were important to us as children.1

The books most mentioned by people as a favourite from their childhood or adolescence were The Lord of the Rings trilogy, but I was surprised by how many people (in what is a particularly geeky group) who had tried to read Tolkien numerous times and wanted to enjoy his work, but hadn’t been able to get into his books.

The Lord of the Rings trilogy and the pleasures of reading aloud

I was previously in this camp. I had tried and tried to read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings at various times in adolescence and adulthood, and had failed each time. It wasn’t until I read The Lord of the Rings aloud to my child that I was able to enjoy Tolkien’s writing. I still haven’t finished reading Le Guin’s book of essays (you will not be surprised to hear), but one of the essays I have enjoyed most so far is ‘Rhythmic Pattern in The Lord of the Rings’ in which Le Guin describes the trilogy as ‘a wonderful book to read aloud…’2

I couldn’t agree more.

Tolkien’s books are a delight to read aloud, slowly. At a walking pace. As an act of endurance. And I mean that fondly. There were many moments of discomfort for me reading the books aloud (all those songs and the poems and that Elvish…). Especially the Tom Bombadil section, which I heartily disliked at the time. But the experience as a whole was one of the highlights of the fourteen or so years I spent reading aloud to my child.

There is a visceral pleasure to reading aloud that silent reading cannot match. As Le Guin writes:3

The narrative prose of such novelists [Dickens, Woolf and Tolkien] is like poetry in that it wants the living voice to speak it, to find its full beauty and power, its subtle music, its rhythmic vitality.

I feel enormous gratitude that my child allowed me to read to them well into their teenage years. We shared so many books together, particularly the classic children’s novels that are less accessible for many children to approach on their own. I read The Secret Garden, A Little Princess and Little Lord Fauntleroy. I read Charlotte’s Web, The Trumpet of the Swan, Treasure Island and the Narnia books. I read Rosemary Sutcliff and Michael Morpurgo (usually through sobs at the end of his books). Reading together is what I miss most of my children’s childhoods, although I am thankful my younger child has grown up into a thoughtful and insightful reader with whom I have many literary conversations.

Reading aloud together isn’t something most adults do these days, although my partner and I have discussed wanting to do so once he is living here. And although I am sure there are places I could go, like schools and nursing homes, where this might be welcomed, I don’t currently have the energy to commit to such an undertaking. But I am thinking through ways I could incorporate this back into my life, partly because it is such an enjoyable way to experience a book and partly for the two reasons I elaborate on below.

Reading aloud and its value for the writer

Reading aloud is a way to better understand good writing. In her essay ‘Stress-Rhythm in Poetry and Prose’ Le Guin writes about the nuanced shifting rhythms of prose.4 If the rhythms of poetry are complex, then those of prose are even harder to pin down. But, as Le Guin writes ‘The thing to remember is that good prose does have a stress-rhythm, subtle and complex and changing though it may be.’5 She goes on to say, regarding the difficulties of understanding rhythms in prose, that ‘The only rule of prose “scansion” I know is: listen to what you are reading (or writing) as closely as you can, listen for its beat, and follow your own ear.’6

There are no rules for finding and feeling the rhythm of prose. It is a gift, but also a learnable skill—learned by practice. Probably the best practice is reading out loud. Ursula K Le Guin

One of the best ways to learn how to write well is to read. Read well. Read widely. Read aloud.

Feeling the words form in your mouth helps you understand what the author is doing. How they are creating the effects that most of us are barely conscious of as we read. I know that many people who enjoy reading do not enjoy ‘pulling the writing apart’ as I have often heard literary analysis called. Which is fine, readers do not need to do this. Writers, however, benefit from it. Learning how a passage is constructed and how different techniques contribute to the effect on the reader is invaluable.

But most of us don’t have time to do that with every book we read, even those of you who enjoy the process as much as I do. And I really, really enjoy it. Reading passages, chapters, even a whole book aloud is possibly the next best thing. Because those aspects of a book, its rhythms and various other techniques, need to be brought more into our conscious minds as we read, so that they are then available to us as we write.

And why should a writer care? Because, as Le Guin writes:7

It is my strong belief … that all prose worth reading is worth reading aloud, and that the rhythms we catch clearly in reading aloud, we also catch unconsciously when reading in silence.

Readers are aware, mostly unconsciously, of the rhythms of our writing. They notice clunky words. They will know when we are mumbling. They will appreciate the pleasure of writing that springs and twirls and glides, rather than prose that stumbles and then treads on their toes.

Read well. Read widely. Read aloud.

Reading aloud and its value for the editor

Reading aloud is an important tool for proofreading. Slowing down and reading what is actually on the page, rather than what you think is on the page, is aided by voicing the words you are reading. If as a writer you have never been told to proofread your work by reading it aloud (to yourself, to a friend, to a patient nearby dog), please do try doing that.

But beyond that, I think reading your work aloud helps shape your writing. In ‘Stress-Rhythm in Poetry and Prose’ Le Guin explains differences in rhythm in the various forms of writing, and suggests a valuable, if somewhat unorthodox, method of finding the rhythms in prose. I will skim over the details, but the key point is to be aware of the stressed syllables. ‘Stress’ in English is that ‘TUM ti TUM ti TUM’ rhythm you can hear in the language. (The stressed syllables are the ‘TUM’ and the unstressed are the ‘ti’.) It is most obvious in verse (’There WAS an old WOMan who LIVED in a SHOE’) but it is there in speech and in prose too. Le Guin writes: ‘If you say more than four unstressed syllables in a row you are likely to find yourself mumbling. That’s what mumbling is.’ She also says: ‘Both as readers and as speakers, we want the stresses to occur fairly often… We don’t really like mumbling.’8

It occurred to me, reading those words, that much of my editing involves removing excess unstressed syllables. Mopping up the naturally meandering rambling mumbling nature of my thoughts as they spill onto the page and drip over the side. And so, I think, for many writers and editors, learning to hear the rhythms (ie the stressed and unstressed syllables) of the prose they are working on is a good first step to making ‘prose dance.’9 Unless you want a mumbling effect, in which case add in those extra unstressed syllables! Writing and creating are about first understanding the rules and then knowing how and when to break them.

Questions for my readers

Over to you, my readers. What were your favourite books when you were young?

Do you ever read aloud these days? Would you like to? Or does the thought fill you with horror (which is very understandable)?

If you are a writer, do you read your own work aloud? Does that help? Do you think reading the work of other writers aloud would improve your own writing?

Let me know in the comments below!

Welcome to all my new readers! It is wonderful to know that so many people are reading and enjoying my writing. To learn more about me, to read the Wondering Steps archives, to manage your subscription and more, click the button below.

If you have enjoyed this post, please hit the heart button at the top or bottom of the page to ‘like’ it. I love reading and responding to comments, so click the little speech bubbles at the top or bottom of the page or the button below to leave me comment!

If you would like to support me and my writing further, please subscribe, if you haven’t already. And please share this post and Wondering Steps with anyone who you think would enjoy it!

Here are the links to my ‘tip jar’ and Amazon wish list, for those who wish to support me in those ways. Thank you so much if you do!

Bye for now! Emma

What a long list mine would be! I’ve never been able to choose favourites or create ranked lists, but my list would include ‘The Little Mermaid’ and ‘Chicken Licken’ as favourite fairy tales, the Faraway Tree books, The Secret Garden, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass (which was the book I chose for this discussion), the Chalet School series and Charlotte Sometimes (beware of spoilers in that link) by Penelope Farmer among others.

Ursula K. Le Guin, ‘Rhythmic Patterns in The Lord of the Rings’ in The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination. (Bolder, Colorado: Shambhala, 2004), p.95.

Le Guin, ‘Rhythmic Patterns in The Lord of the Rings’, p.95.

Ursula K. Le Guin, ‘Stress-Rhythm in Poetry and Prose’ in The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination. (Bolder, Colorado: Shambhala, 2004).

Le Guin, ‘Stress-Rhythm in Poetry and Prose’, p.79.

Le Guin, p.80.

Le Guin, p.81.

Le Guin, p.73.

Le Guin, p.80.

I read aloud, my own work mostly, once it's at the final edits stage I read it to my partner.

My favourite memory of reading aloud as an adult was with a wonderful boyfriend called Stephen. We read Good Omens by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman together but halfway through had to go off to different places for Christmas. He couldn't wait to carry on, so he recording himself reading it for me!

Seconding your advice on reading your own writing aloud! It's the number one editing tip I give students (not just for the proofreading bit) but because your ear catches things that your brain doesn't. It's a good reminder I should be doing that more with my own work, too.